Tuesday, May 14, 2013

Joseph Lister – founder of antiseptics

Joseph Lister, an English doctor, was born at Upton, Great Britain, in 1827. He was the first to discover

the reasons for infection and is known as the founder of antiseptic* surgery. As a child Joseph was a healthy

and good-looking boy. He was the fourth of seven children. His father was a well-known scientist. Joseph

loved to ride his father’s horses, play cricket and go skating with his brothers and sisters. Like his father,

Joseph became interested in science. While still at school, he began to cut up animals and it was clear that

he was born to be a surgeon. At the age of twelve, Joseph was sent to a special school where he began to

study anatomy. While the other boys were out playing, Joseph was drawing various parts of the human

body and was giving names to the bones. Anatomy interested him so much that at the age of fourteen he

told his father he wanted to become a surgeon. His father did all he could to give his son a good start in his

career. When he was seventeen, Joseph Lister was sent to University College in London.

At first Joseph was not happy in London. He did not like London and missed his countryside, but soon he

became deeply involved in his work. Joseph’s medical training lasted for nearly eight years. Afterwards,

following his professor’s advice, Joseph started to work at one of the famous medical schools in Edinburgh,

Scotland. He intended to stay there for only a month but stayed for seven years! He assisted his professor in

performing operations. At that time, it was no secret that, after operations, many patients died. This

happened because no one knew how the surgery instruments had to be treated correctly. Along with giving

lectures, Joseph studied how to prevent infection from spreading. He did not like lecturing because it took

him a long time to prepare his classes. But little by little Lister got accustomed to it and became an

extremely good lecturer. He no longer read his lectures but spoke with the help of a few notes. Joseph Lister

soon had a class of nearly 200 students, which was the largest medical class in the country. Then he was

asked to take charge of the surgical section of Glasgow’s Royal Hospital. He accepted the offer because

now he had more time for scientific research. It was there that Joseph Lister carried out the revolutionary

work for which he is now famous: he found the causes of infection.

Making automobiles

By 1890 factories in the middle west of the United States were making parts for a new machine –

the automobile. The car parts were transported to workshops where workers put them together to

make cars. But it took a worker twelve hours to assemble one car and, since cars took so long to build,

the people who made them had to charge their customers a lot of money to buy them. So only people

with a high income could afford to buy a car. Then a man from Michigan named Henry Ford thought

of a way to make cars more quickly. Henry Ford was from a farmer’s family. He left school at the age

of fifteen to work on his father’s farm but he disliked farming and spent his spare time trying to build a

petrol-driven motor-car. His first car, finished in 1896, was built in his garden and was named Tin

Lizzie. In 1909 Ford decided to manufacture only one type of car, the Model T. At first it took fourteen

hours to assemble a Model T car but, by improving his mass production methods, Ford reduced this to

one hour and 33 minutes.

Henry Ford’s idea was to use many workers instead of just one to build each car. He divided the job of

building cars into hundreds of steps, and he hired one worker to do each step. Then he set up a moving

belt that carried a line of unfinished cars past each worker. As each car reached each worker, the belt

would stop moving. It would stop just long enough for the worker to do his one task. Then it would carry

the car along to the next worker. This way of building cars became known as ‘the moving assembly

line’.

Workers on the moving assembly line only had to stand in one place and do the same job over and over

again. Most workers could learn their job in almost no time. Working together on the assembly line, they

could build a car in an hour and a half. By using this new moving belt technology, Ford was able to

reduce the cost of each car and between 1908 and 1916 the sale price of a Model T car fell from 1000 to

360 US dollars. About one million Model T cars were produced in 1921 and, in less than twenty years,

the automobile took the place of the horse-drawn carriage. Henry Ford produced an affordable car, paid

high salaries to his workers and helped to build a middle class in America. He left his mark on the

history of the USA.

The world’s mysterious places

Developments in archaeology have led to fascinating discoveries. Scientists have discovered objects or

places that tell us a lot about how some of the world’s oldest cultures lived. There are places, though, that

have been the subject of much discussion among scientists. Three of the most mysterious places are Easter

Island, Stonehenge and the Nazca Desert.

Located in the South of the Pacific Ocean, Easter Island is one of the most isolated places on earth and is

famous for about 600 large stone statues that are lined along the coast. These structures, which were carved

by ancient people and which look like human heads, are from three and a half to twelve metres high. On the

opposite side of the world stands Stonehenge. This ancient English site is a collection of large stones

arranged in two circles, one inside the other. Archaeologists believe that the inner circle of stones, each

weighing about four tons, was built first. The giant stones which form the outer circle, known as sarsen

stones, each weighs as much as 50 tons!

In South America, one more mysterious phenomenon exists. Near the coast of Peru, in the valley of the

Nazca Desert, some strange shapes carved into the ground make an impressive view. When seen from the

ground, these shapes seem insignificant. But when seen from high above, these strange shapes or drawings

look like giant birds, fish, seashells and different geometric figures. These drawings are thought to be at least

1500 years old, and have still remained preserved for centuries by the dry, stable climate of the desert.

Many theories exist about the ancient peoples of Easter Island and the Nazca Desert and their purposes in

creating these mysterious phenomena. Archaeological research suggests that Easter Island was first inhabited

by Polynesians around 400 AD. Scientists believe that these early inhabitants carved the island’s statues as

religious symbols from a volcanic rock and then pulled them to different locations. Scientists suggest as well

that the lines of Nazca are also related to the religious beliefs of an ancient civilization. These people

believed that the mountain gods protected them by controlling the weather and supplying them with water.

Many of the figures formed by the lines on the ground are associated with nature or water in some way. As

these ancient people lived in a desert region, water was a valuable, but rare, resource and by means of the

drawings they hoped to make the place rich with water. Exactly how the lines were drawn without

controlling the drawing process from the air remains a mystery.

We may never know the exact reasons for the creation of these mysterious places. Whatever their original

purposes, all three sites are amazing examples of human creativity.

Labels:

world

The Great Library of Alexandria

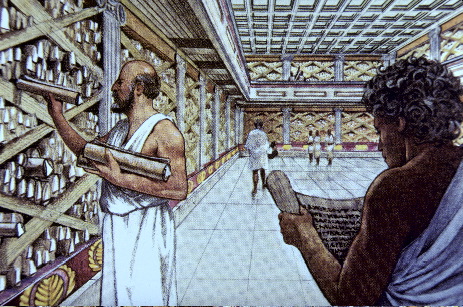

Though public libraries first appeared in the fourth century BC, private libraries were quite common in

those times as well. Aristotle, for instance, had a large private collection. The ancient geographer Strabo

wrote: ‘Aristotle was the first to put together a collection of books and to teach the Egyptian kings how

to arrange a library’. That library, of course, was the Great Library of Alexandria. The Great Library of

Alexandria no longer exists, but it is not known for sure when the library was destroyed or who

destroyed it.

Julius Caesar is traditionally accused of demolishing the library in Alexandria. It is true that Julius

Caesar invaded Alexandria in 48-47 BC and his army set the fleet of ships in Alexandria harbour on fire.

Some historians believe that this fire in the harbour spread into the city of Alexandria and burned the

library down. However, there is hardly any evidence to prove this fact. The conclusion which seems to

be most accepted today is that the library in Alexandria existed, at least in part, four centuries after the

death of Julius Caesar. At that time, at the end of the fourth century AD, there was a general movement

to destroy temples and libraries and it seems more likely that the Alexandria library was destroyed at that

time.

The library of Alexandria is believed to have been a magnificent building housing the greatest collection

of scientific works of the time. It was founded by Ptolemy I, the General whom Alexander the Great

appointed as the ruler of the city named after him. It was Ptolemy’s son, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who

decided to expand the library and succeeded in making it famous for its unique collection of

manuscripts. Under Ptolemy II and those who followed, the library continued to expand. Ptolemy II

wanted to create a library containing every Greek work ever written, as well as all the works from other

parts of the Western world that could be gathered together. The number of manuscripts in the library is

thought to have been between 300 000 and 700 000.

As each manuscript had to be copied by hand, a huge number of people were employed in preparing

manuscripts for the library. Manuscripts were bought, borrowed or taken from all over the Western

world to be copied and placed in the library. However, it was quite common to copy an original

manuscript, to return the copy to the owner and to keep the original for the library. Manuscripts were

often received from foreign powers in return for traded goods. Forcing citizens to pay their debts to the

government by giving manuscripts was also very common. It was in these ways that so many

manuscripts were collected in the library of Alexandria.

Labels:

Art

History of Cinema

In December 1895 the Lumiere brothers projected the first film onto a screen for a paying audience and

cinema was born. That simple, silent show took place in a hotel basement in California. Most early films

were shown at music halls or fairgrounds. In 1905 the first ‘nickelodeon’ opened in Pittsburgh in the USA.

This was a cinema which charged a nickel (5 cents) for admission. Within three years there were 5000

‘nickelodeons’ throughout America. Going to the movies soon became a popular pastime around the world.

With their richly designed interior, cinemas gave audiences a chance to observe the luxurious lives of the

characters on the screen. But not all cinemas were glamorous. Small movie theatres in local neighbourhoods

were often cramped and dirty. In many countries, travelling projectionists toured the countryside showing

films on transportable screens in village halls or even outdoors.

Talking pictures arrived in 1927, and films became more popular than ever. Millions of people went to the

movies during the 1930s, often several times a week. Along with the main feature film, audiences could see

a cartoon or a documentary about interesting people, places or wildlife. Before there was news on

television, the news of the week was presented in film ‘newsreels’. During World War Two, people saw the

latest battles on newsreels at their local cinemas. After the war people stopped going to the cinema so

regularly. Cinema’s biggest rival was television. In order to attract more audience, film-makers began to use

expensive technology which TV could not compete with. A growing number of films were made in

technicolour and stereophonic sound was used. Wide-screen films set in ancient or biblical times, with huge

number of actors and expensive sets and costumes, were popular throughout the 1950s. People could even

watch films from inside their cars at huge outdoor ‘drive-in’ cinemas. Films shot in 3-D were less

successful, as audiences disliked wearing special glasses.

In spite of the new technology, in the 1960s attendances continued to drop. Thousands of cinemas

throughout the world were forced to close. Some of the bigger theatres were divided up into a number of

smaller cinemas. In the mid-1970s, big budget blockbusters, packed with fast-moving action and special

effects, began to attract a new generation of young film-goers. When these movies were released on video

cassettes, people had the chance to own their favourite films for the first time. The invention of digital

video has made it possible to store moving images on compact disks. When the films are played on special

CD ROM and DVD systems, viewers can not only watch the action on the screen, but also interact with it.

Soon it will be possible to change the story lines of films and even act in them yourself!

Labels:

Art

Edward Jenner the father of vaccination

Edward Jenner, an English doctor, is known in the history of medicine as the person who discovered

vaccination. He was born in 1749 in a rural part of Great Britain. Jenner was a country boy and he loved the

quiet village he lived in. As a child Jenner liked to observe and investigate things. His favourite pastime

was studying nature and he loved and understood country life.

In Jenner’s times people all over the world were affected by a disease called smallpox*. Many of them had

the marks of the disease on their faces. But those were the people who had recovered from the disease;

many more used to die. In the eighteenth century, smallpox was one of the main causes of death and it was

common among both young and old. Of all the diseases at that time, smallpox was the worst.

Edward Jenner was a man who was always trying to gain knowledge wherever he could. Nothing ever

escaped his sight and hearing. Years before, he had heard a milkmaid say, ‘I can’t catch smallpox, I’ve had

the cowpox*.’ At first Jenner mentioned the milkmaid’s words to Dr. Ludlow, whose student he was. But

the doctor only laughed. Jenner did not say anything but he continued to ask himself how the harmless

cowpox could save people from smallpox. He believed that science had no limits and a scientist had to be

patient to succeed.

After years of trying, Jenner’s efforts to find a cure for this disease were not successful. Then one day he

decided to try an experiment and he rubbed some of the cowpox substance into a village boy’s cut. A few

weeks later he repeated it but this time with smallpox substance. The result was that the boy remained

healthy. Overcoming lots of difficulties, Jenner repeated his experiment twenty-three times, with the same

result. It was only then that he believed in his discovery and published the results. Jenner’s discovery of

vaccination against smallpox was one of the greatest discoveries in the history of medicine. In 1798 he

published a report, calling his new method ‘vaccination’, from the Latin word vacca, meaning a cow. At

first people paid no attention to the work of the country doctor. Some even said that vaccination might

cause people to get cows’ faces!

Soon the news of the wonderful discovery spread abroad and terrible smallpox began to disappear as if by

magic. Jenner was extremely happy to finally read a report saying that for two years there had been no cases

of smallpox in any part of the world. Edward Jenner died in 1823 at the age of seventy-four. Till the end of

his life, the ‘country doctor’ lived simply, spending on research the money the nation’s Parliament gave

him, and vaccinating free of charge anyone who came to him

Labels:

Science

The history of chocolate

Many of us love chocolate and many countries make different kinds of chocolates as well as products in

which chocolate is an important ingredient. For some countries, like France or Switzerland, chocolate is one

of the main exports, bringing to these countries hundreds of thousands of dollars. But not many of us know

much about how chocolate is produced or about the history of chocolate and the chocolate making industry.

Chocolate is a kind of food that is made from the seeds of the theobroma cacao tree. ‘Theobroma’ is a

Greek word meaning ‘food of the gods’. The tree originally comes from the Amazon region of South

America. Hand-sized pods that grow in the tree contain cacao seeds - often called ‘cocoa beans’. These

seeds or beans are used to make chocolate. They started to use cocoa beans around 1000 BC. Later, the

Mayan and Aztec civilisations made a drink from cocoa seeds. They often flavoured it with ingredients such

as chili peppers and other spices. Drinking cups of chocolate was an important part of Mayan rituals such as

wedding ceremonies. People also believed that eating cocoa beans had positive effects on health. For

example, in Peru eating or drinking a mixture of chocolate and chili was said to be good for your stomach.

The Aztecs thought that it cured sicknesses such as diarrhea and one story says that their ruler, Montezuma,

drank fifty cups of cocoa drink a day.

Christopher Columbus, with his Spanish explorers, made his fourth trip across the Atlantic in the early

1500s, and arrived on the coast of Honduras, in Central America. There he discovered the value of cocoa

beans, which were used as money in many places. In the sixteenth century, another Spanish explorer named

Herman Cortez took chocolate back to Spain. The Spanish people added other ingredients such as sugar and

vanilla to make it sweet, and sweet chocolate remained a Spanish secret for almost a hundred years.

Chocolate finally spread to France in the seventeenth century after the marriage of Louis XIII to the Spanish

princess Anna, who loved chocolate. In about 1700, the English developed a new drink using chocolate and

milk, which became very fashionable. The popularity of chocolate continued to spread farther across

Europe and the American continent. The only Asian country to use it at that time was the Philippines, where

chocolate had been introduced by the Spanish when they invaded the country in the sixteenth century.

As chocolate became more popular, there was an increasing demand for people to work on the cocoa

plantations. Slaves were brought from Africa to the American continent specially to farm the cocoa. Later,

the cacao tree was taken to Africa and cultivation of the cocoa beans began there. Today, African

plantations provide almost seventy percent of the world’s cocoa, compared with one and a half percent from

Mexico.

Labels:

Delicious

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)